Society

11.13.2018

Certain Arabic Speakers Can’t Understand Others. Here’s Why

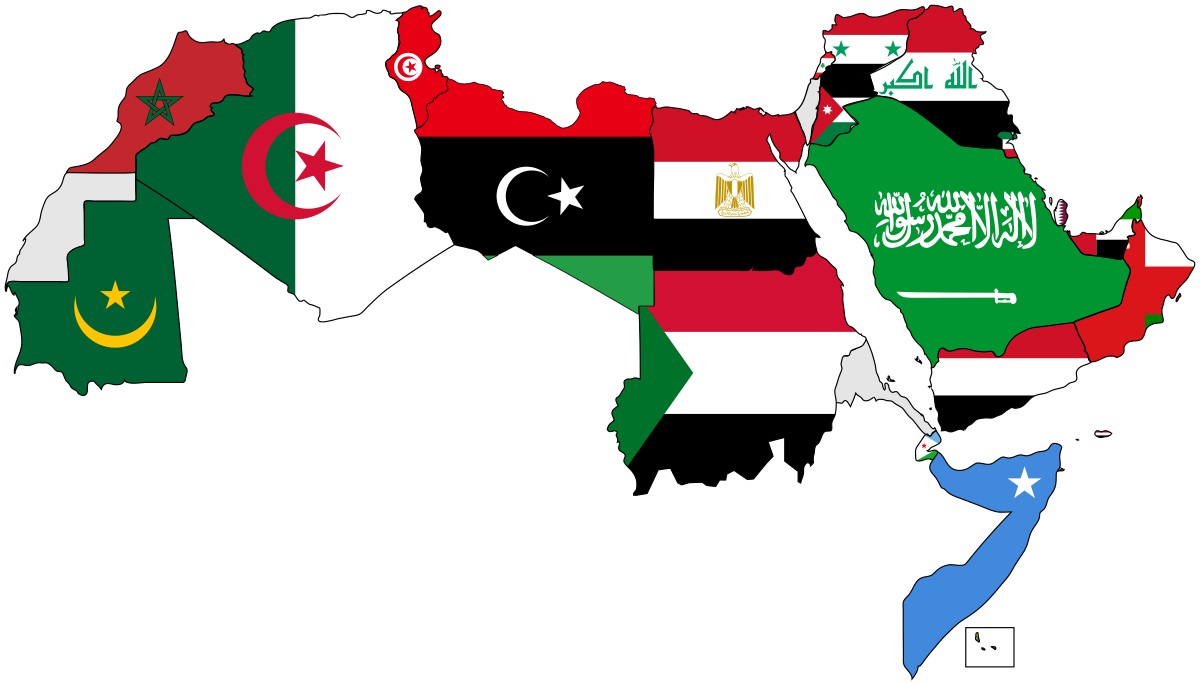

The crucial, basic choice any person makes when they decide to learn to speak the Arabic language is: Which one?

A question of taste

One opinion is that Lebanese Arabic is the prettiest spoken form of the language. Another one is that people in Saudi Arabia articulate Arabic the most clearly. And many are astounded by the amount of Spanish that has entered the Moroccan vernacular.

Egyptian cinema boasts three fourths of the films produced in the whole MENA region. So it’s no surprise that people find the ability to mimic the Egyptian dialect as the coolest party trick. Think of an old Hollywood star’s golden age accent. Today, Egyptian Arabic is the dialect used by most contemporary non-Egyptian pop singers in the Middle East, and the more classical musicians before that, too. These factors make the Egyptian accent simply cooler than the rest.

But beyond the accents

The reality of spoken Arabic today is a little more complex. Accents are one thing, but structure and comprehension are a whole other issue. Although native speakers, they’re essentially not speaking the same language.

Each country has its own dialect. And within each country is a distinct set of sub-dialects, with their own vocabulary and grammar rules.

Going back to the vast Saudi kingdom, experts count up to 23 distinct accents. Locals from coastal Jeddah may speak certain words with an almost Egyptian accent. Jeddah, after all, is geographically closer to Egyptian soil than it is to Najd, the region which hosts the Saudi capital, Riyadh. So the dialect changes taking place from region to region happen in a geographically logical manner.

Quirky qualifiers

A Tunisian person would say “bahebbek barsha” to mean “I love you very much”. A Sudanese person would say “bahebbek shadeed”. Barsha and shadeed, both qualifiers, mean “very much”, but are never used in the same way by people from those countries.

In fact, the word barsha, is practically unused by anyone living outside of Tunisia. And the list goes on: an Emirati person would use marrah, or maybe even katheer. A Lebanese person would say kteer, but never marrah.

But when it comes to the basics, an Algerian will be able to express joy when speaking to a Syrian. And when they’re on a trip abroad, Arab tourists from Dubai are generally able to order food in a tourist hotspot in Marrakech.

But what about effective communication?

For that, knowledge of classical Arabic is key. And all high schools (which teach Arabic of course) teach the same classical Arabic in class.

So many Arabs who have attended Arabic classes can defer back to classical Arabic when needed, guaranteeing a certain degree of comprehension when a tourist is lost.

This transversal, persistent quality of classical Arabic allows Omani residents to listen to radio shows from Jordan with no issues.

Pro tip: for the record, the classical Arabic phrase for “I love you very much” in the romantic scenario described above, would be uhibbuk(i) kathiran with the “i” added when speaking to a female.

And what’s next?

In the end, despite the plethora of largely undocumented linguistic quirks and differences, it’s okay. Arabic is just evolving with our modern, digital and globalized times.

In Morocco, certain media outlets now publish articles in dialectal Arabic, generally a no-no in other, more Eastern countries.

Young and old people texting will use Latin letters, such as 3 and 9 to write sounds that the alphabet doesn’t accommodate. This heralds a trailblazing future for Arabic to continue evolving, organically, as a tool to serve its user.

The great thing is that Arabs generally are aware of the other accents that surround them, and appreciate their differences. But the complexity of spoken Arabic remains both a highly nuanced and largely undocumented phenomenon.

popular