Lifestyle

12.2.2019

Farah Foudeh: “I think that images have a huge impact on the way we understand history, people and places”

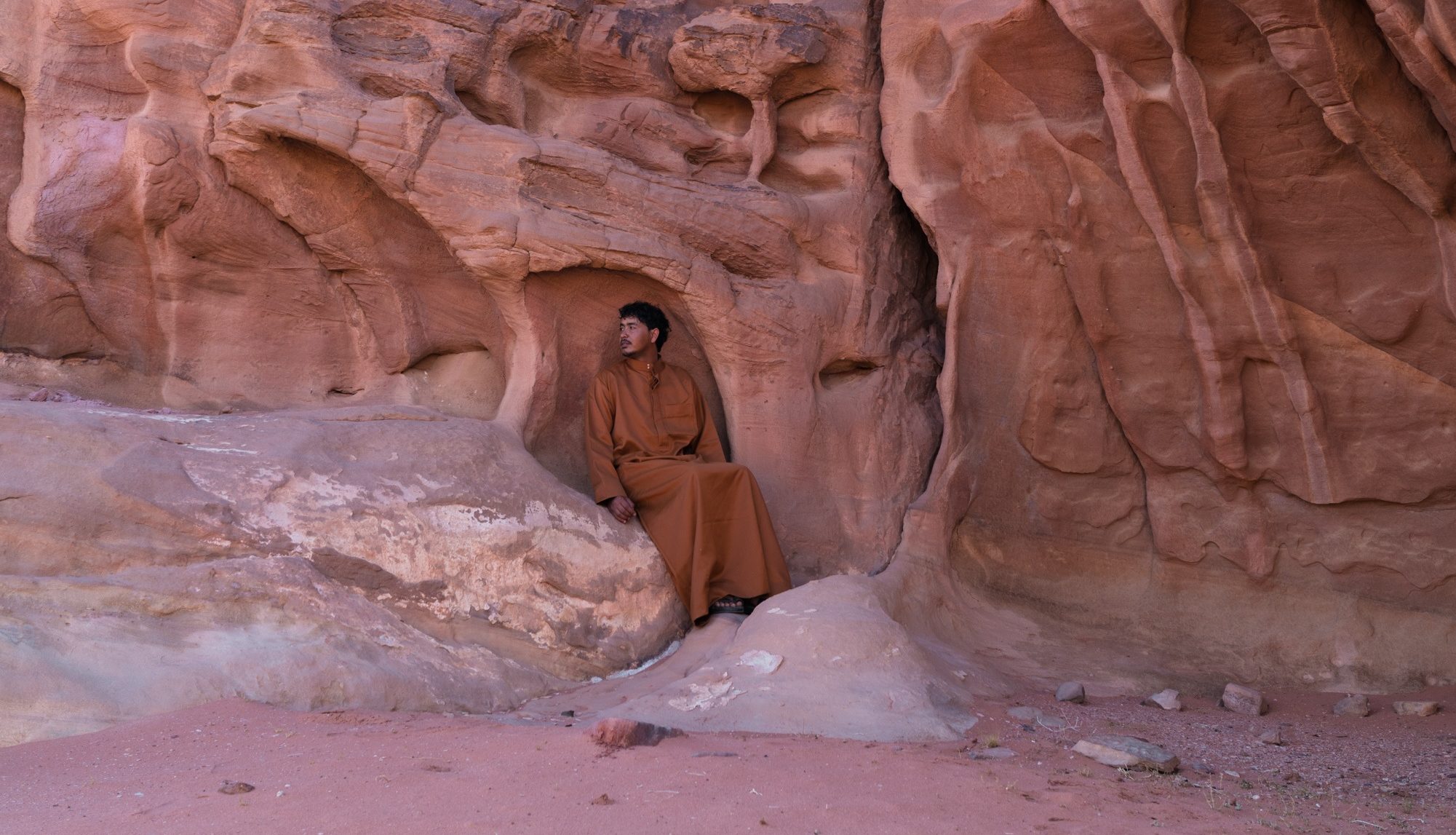

“The Bedouin man has been photographically presented and reproduced under the same lens. It is almost as if time stopped when it arrived to Jordan, and I wanted to play on this image.”

Farah Foudeh likes to play with images. For her, photography is a playful tool that allows one to observe life with different perspectives, reflect on communities, and question identities in a way that will change “already made” perceptions. Very much rooted in her Palestinian heritage, yet her work goes further to explore humankind’s relationship to identity in an almost philosophical journey. Fascinated by the image of the bedouins in Jordan, she delves into their surroundings and the way tourism impacted their reality.

For this she followed few young men in the Wadi Rum desert with her series “Bedu”, and more recently in Petra, through “It takes two”, a body of work that spread over the last two years and that explores how mass tourism impacts the social landscapes of Petra in a unique mixture of seclusion and openness.

How your nomadic lifestyle inspired your work?

Growing up as a ‘foreigner’ in a city in Nigeria and further living out this role in every other city I have lived in has given me the privilege of a detached perspective when it comes to defining identity. It has made me really interested in exploring questions of identity and exploring how people come to define themselves. In my life, identity has always been something fluid, yet all grounded by a very strong core; my Palestinian heritage. In my work, I am attracted by communities that share a similar core. I investigate how this relationship with a place can mold and shape a sense of identity. The communities I have worked within Petra and Wadi Rum are very closely defined by their place of origin. It inspires me to draw up portraits of my subjects by trying to understand the whole picture of the space they inhabit and how space inhabits them.

What triggered your photographic series “Bedu”?

I think images have an immense impact on the way we understand history, people and places, in ways that we might not be consciously aware of. Bedu is my earliest work and came at a time when I was very wary of photography and its effects. I was inspired by the continuous representation of Jordan in the context of tourism, through the image of the Bedouin. The Bedouin man has been photographically presented and reproduced under the same lens. It is almost as if time stopped when it arrived in Jordan, and I wanted to play on this image. I played on the traditional cliché images of the Bedu in Wadi Rum while exaggerating the gestures. I wanted to create a work that was clearly staged, yet gives the viewer the chance to question the authenticity of the images.

How did you manage to break the stereotypes through your pictures?

I would not say the images themselves break the stereotypes. What they do is play on the stereotype and give the viewer the chance to make that distinction. Someone might look at my photos and not think twice about it, others might be intrigued by the underlying undertones of the images and seek answers through texts. I use photography as an initial tool to start important conversations, the other part of my work comes in forms such as these, interviews and talks. There’s a lot that needs to be addressed and it cannot all be solved through an image.

You said in a newspaper “I believe that by ‘othering’ a people you create a somewhat dangerous distance in which a lot can happen”. How do you think western media and societies represent the Arab world today?

I think we have two main sources of information when it comes to Arab countries and societies. The first is through the media, which focuses on war and terror. The other is through tourism, which focuses on cliches and stereotypes. The media is driven by stories of extreme violence while tourism is driven by the pursuit of exotic imagery and experiences. Both views can be quite harmful, and in a way complement each other in creating a space for further misinformation. The tourist perspective represents the country through the image of it’s past, sending out a message that the place or people are inherently different (than them as developed westerners), as they are still living in the past. While the media is continuously reporting on the war in certain countries in the Middle East, which seems to be unrelatable in today’s western societies. What these two perspectives are indirectly creating is a line between US and THEM. One the one hand society is fetishizing the Arab world, while the media is demonizing us. Both are different forms of othering.

The global #metoo movement is shaking our conception of genders and also feminism all over the world. As women with Arab roots, do you feel that Arab women are not enough represented or misrepresented in those feminist movements ?

This is a sort of a sensitive topic for me. As an Arab woman myself, I feel like most Arab feminist work is done/created with a western audience in mind. We are either trying to create an image of a strong empowered woman to shatter stereotypes, or we are portraying cases of extreme inequality to show the harsh reality of life for many women in the Middle East. There is a lot happening in between that is lost and we are not really speaking to the Arab woman herself. I believe that translates to feminist movements, it should not be about including Arab women in already established feminist movements in western contexts. It is about having these local movements coming from the Arab world itself.

See also

undefinedpopular